An Interior Ellis Island (Print Version)

Immigration, Ethnicity and the Peopling of the Copper Country:

An Interior Ellis Island

Close

| Finnish Dress Image #: Nara 42-174 |

The past does not speak for itself, it is spoken for, and there is little in the remains of mineshafts, rock piles or other physical evidence that exists today to tell the story of the peopling of the Michigan’s Copper Country. Nothing remains in the Copper Country to tell us that at the turn of the century, the Keweenaw Peninsula was the most ethnically diverse community in Michigan. Indeed, it was among the most ethnically diverse places in the United States. The 1870 Federal Census reveals that Houghton County, with 57% of its population foreign-born, had the third largest foreign-born population as a percent of the total population in the United States. While in that year 71% percent of Americans had native-born parents, fewer than 5 % of Houghton County residents could make such a claim. Again, for prospective, Houghton County with 96% of its population with at least one parent of foreign birth had the greatest such percentage in the entire United States. According to one child of immigrants, the claim of native-born parentage and Americanization held a negative connation for the residents of the Copper Country:

There ain’t no natives on the [Keweenaw] range. We’re all foreigners up here. Sure I was born here; but my folks came from Ireland and they stayed Irish until the day we buried the two of them. Them Swedes, them Austrians and Polish, they’re all the same way. . . . What I mean, we’re different from those people downstate [Lower Peninsula]. Hell’s fire, half them fellows in Lansing are ashamed their folks come from Europe. Look at the way they changed their names. You don’t see that stuff on the range. . . . We ain’t the same as those stuck-ups downstate. That’s why I say we’re foreigners.

The people of the Copper Country were indeed different from the people of Michigan’s Lower Peninsula as pre-automobile Michigan had very little ethnic diversity. Due to the Erie Canal, New Englanders from western New York, or those migrating directly from New England, mainly settled the state. The agriculture-dominated economy of this “Yankee Michigan,” drew few immigrants and even fewer from eastern and southern Europe. The exception to this nineteenth-century Yankee Michigan was its Upper Peninsula and more specifically its Keweenaw Peninsula. Indeed, in 1900, Houghton County had the largest Chinese, Italian, Finnish, Slovenian and Croatian communities in Michigan. The Calumet public schools claimed to have enrolled children from forty different nationalities from around the world.

The ethnic composition of the Copper Country dramatically changed over time. Initially, the Keweenaw Peninsula drew its labor chiefly from the British Isles, Western Europe and Canada then, after 1890, largely from southern and eastern Europe. In 1870, the Irish were the single largest immigrant group, accounting for nearly a third of the entire foreign-born population in Houghton County, followed by the Cornish, French Canadians and Germans. By 1880, the Cornish were the single largest immigrant group followed by the French Canadians, Irish and Germans. In 1890, the Finns emerged as the single largest immigrant group, a position they would never relinquish, followed by the French Canadians and the Cornish. By the turn of the century, the Finns accounted for a quarter of the entire foreign-born population in Houghton County, followed by the Cornish, French Canadians and the rapidly arriving Croatians and Slovenians, many of who were enumerated as “Austrians.” In 1910, the Finns accounted for a third of the entire foreign-born population, followed by the Cornish, “Austrians,” and Italians.

The peopling of the Copper Country, like all migration, was an economic process driven by “push factors” and “pull factors,” that is, people were pushed out of areas that experienced high levels of surplus labor and pulled to areas that experienced labor shortages. With exception of the Cornish, Irish and some Germans who arrived with previous mining experience, most of those who peopled the Copper Country emigrated from rural parts of Europe that were experiencing and economic upheaval. During the last half of the nineteenth century, most of Europe underwent the capitalist transformation of agriculture. This shift toward market-oriented agriculture demanded greater mechanization and thus capital investment. This process placed tremendous economic pressure on small landholders, who, because they lacked capital, increasingly could not compete in a market with larger landowners. Simultaneously, mechanization reduced the need for their labor as well as the labor of their less fortunate neighbors who were landless peasants. As such, the capitalist transformation of agriculture in Europe produced large numbers of people who either became unemployed or underemployed (surplus units of labor) or small landholders with insufficient land to survive. In search of work, many peasants were forced to migrate to areas with labor shortages in Europe and the United States.

Copper mining, of course, with its great demand for labor was the “pull factor” that drew these emigrants to the Keweenaw. Yet, this begs the question: why were the mine owners unable to attract sufficient native-born labor? During the last half of the nineteenth century and into the twentieth century, there existed a dual labor market in America, that is, a secondary labor market was created by the difficulty or danger of certain industrial occupations that few native-born or English speaking people from the British Isles would fill. Indeed, in 1910 the US Senate Committee on Immigration asked mine owners in the Copper Country why they needed so many foreign workers? Apologetically and remorsefully, they replied: “. . . the employment of these races [from southern and eastern Europe] is due principally to the fact the supply of English-speaking workingmen has not equaled the demand for labor and that it has been necessary, in order to operate the mines, to have recourse to this source of labor supply.”

This remarkable influx of immigrants dramatically impacted the development of the Copper Country, but it also significantly impacted the sending communities from which they emigrated. Brinje, a small town in Croatia of around 5,000 people, sent over 700 young men to work for the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company. Emigration on such levels radically altered the lives of those who remained in Brinje. Excerpts from a 1905 letter from a Croatian schoolteacher offers glimpse in of the lives of those left behind:

Today they are telling in the village that fifteen are going to Fiume tomorrow by the early train, - men, women, and young girls on their way to America. They took leave of the fatherland, our dear Croatia . . She must let them go among strangers in order that those who remain may live, they and their children and their old people. And the old people die in peace because they have hope; the little ones shall fare better than ever they have done.

Toward evening they can be seen hurrying from house to house, taking leave of those that they love. Who can say that there will ever be another meeting for them? It is very late before they have finished these visits, and the family waits for them with impatience. With impatience, how else, when this evening or rather the few hours still left are so short. This is the last supper at home. There is no going to bed, for at three they must start for the station, as the train goes at four. It is so sad to hear them driving through the village singing a song which expresses all the feelings of their sore hearts.

The saddest moment of all is the departure. The train has come, they must get on board. How many tears and sobs and kisses in our little forest and rock-bound station! Friends go with them to Fiume -- all but the children and the old folks, who stay in the village alone. Often the parents buy the betrothal rings for their sons and daughters, who marry in America, and send them to them. Faith and love come from the homeland. Finally, at the ship good-byes must be said, the lastWith what anxiety and joy do they wait for the news from the agent that their dear ones have reached New York in safety? There, relatives are already expecting them, and the journey can be peacefully continued in their company. Our people generally go to Michigan. In one town there are so many that our people call it "New Lipa."

Twenty years ago two men went to America from here, the first from our place to go. Now nearly half the village is in America. It is hard to till the fields, for there are no workers to be had. Whoever has strength and youth is at work in America. At home are only the old men and women, and the young wives with their children.

This letter reminds us of the role that immigrants played in supporting their sending communities, the world they behind and the pain of emigration. Such heartbreak, of course, was not limited to Croatia. Many experienced the tears and sobs and kisses in places like Berehaven Ireland, Camborne Cornwall, Jolitte Quebec, Bramberg Germany, Pajala Sweden, Tronhiem Norway, San Gergio Italy, Wasalan Finland and in hundreds of towns and villages throughout the world.

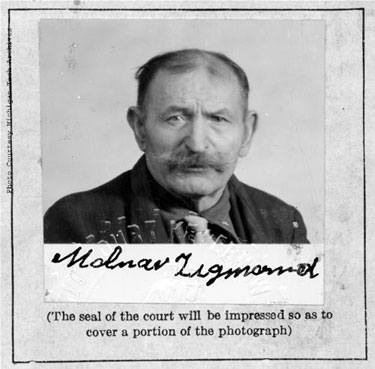

| Malnar Zigmond Image #: No Neg 06-06-23-002 |

In addition to the exceeding large foreign-born population in the Copper Country, the children and grandchildren of the foreign-born constituted much larger ethnic groups. In her examination of ethnicity among Americans of European descent in the years after the Second World War, sociologist Mary Waters has convincingly argued that their ethnicity has largely transformed itself into choice. That is to say, for present day Americans of European ancestry, their ethnicity is more a matter of consent than descent. This is an important point to our understanding of ethnicity in the United States in the years between 1870-1930; ethnicity was not a choice. This appears to have particularly true in the Copper Country where newspapers listed one’s ethnicity next to one’s name, or, quite frequently, did not bother to list one’s name at all and simply referred to an individual as an “Irishman,” a “Finnish trammer,” or a “Croatian laborer.” Documents such as the Houghton County Jail Records suggest that ethnicity had a pseudo-legal status into the twentieth century, as the ethnicity of inmates, not place of birth, was indicated next to their names. So to was the case with the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company and the Quincy Mining Company as both had their workers identified by ethnicity on their employment records. During the 1913-14 Strike, C & H produced bi-weekly reports that enumerated the ethnic differential of striking and non-striking workers. Even more extraordinary, C & H produced monthly reports on the ethnic composition of their workers into the 1950s. So, for instance, the head of C & H could know the exact number of Italian trammers, French Canadian mill workers or Finnish miners on May 1, 1950 and the increase or decrease of a given ethnic group from last month in a given job category. Needless to say, C & H had the forms specially printed, as these were not standard business forms in the 1950s.

What such forms, and the worldview that they represented, could not account for, of course, was inter-ethnic marriage. There existed no column for someone who was part German and Irish, someone who was past Finnish part Slovenian, or perhaps someone who was part German, Irish, Finnish and Slovenian. Ruby Jo Kennedy, a sociologist who published in 1944 an article “Single or Triple Melting Pot? on intermarriage in New Haven, Connecticut observed a shift beginning in which people were moving away from marring within their ethnic group to marring within a religion, usually in the third generation. This process might have begun earlier in the Copper Country. A small study of 500 households in Calumet found that in 1910 twenty percent of all marriages were interethnic. The Irish (66%) were the most likely marry someone outside their ethnic group, followed by the French Canadians, Swedes and the Cornish. Conversely, the Croatians (4%) were the least likely marry someone outside their ethnic group, followed by Finns, Italians and Slovenes.

The 1913 Copper Strike was the Keweenaw Range’s defining moment. The strike was in many ways an ethnic conflict as much as it was struggle between labor and capital, workers and mine owners. In general, the newly arrived ethnic groups from southern and eastern Europe were more likely to support the strike, while the established ethnic groups from northern and western Europe were less likely to support the strike. Croatian workers were the least likely to go back to work, followed by the Hungarians, Bulgarians and Finns. Conversely, the Cornish were the least likely to strike, followed by the Scots, Germans and Scandinavians. When the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company attempted to resume underground operations in September 1913, an astonishing 94% of Croatians continued to strike, compared to only 40% of the total workforce. Croatians and Finns, with 63%, were the only ethnic groups that had a majority of their workers who refused to return to work. By the middle of December, 86% of C&H’s Croatian workforce still remained on strike, and, as such, they were the only ethnic group that had a majority of their workers out on strike. By the end of February 1914, when the strike was clearly lost, 84% of the Croatians continued to strike; the Finns with 24% were the nearest ethnic group showing such solidarity.

Mining on the Keweenaw, like all extractive industries, declined and ended. Just as the Copper Country saw tremendous immigration it also experienced tremendous out migration. As mining declined so did the need for labor and just as the Keweenaw began to experience high levels of surplus labor, the auto industry began to experience a near insatiable demand for labor. Most anecdotal evidence suggests that Detroit and southeastern Michigan were the main recipient of the Keweenaw’s out migration. Again, the “push-pull” mechanism of labor migration drove this process. The ethnic composition of the Copper Country not only resulted from in migration but out migration as well, as not all ethnic groups out migrated at the same rate. The Finns appeared the least likely to leave the Copper Country, while the Croatians and Italians were the most likely to out migrate. In general, the immigrants (the parents or their children) remained while their children or grandchildren left. Thus, the Keweenaw Peninsula served as an interior Ellis Island, that is, an entry point for tens of thousands immigrants and their children into American society.

Back in the 1990s, an often-heated debate emerged within the pages in the Mining Journal regarding the placement of Finnish names on street signs in Hancock. The issue brought the question of the Copper Country’s ethnic identity into sharp focus as non-Finns wrote and expressed a sense that the Finns were expropriating the Copper Country, pointing out that they were not Finns and that their ancestors had arrive from a certain country at a certain date and worked hard in the mines. Finns often enough responded that such sentiments were anti-Finnish bigotry, which had long history in the Copper Country and generally had that such anti-Finnish bigotry had its origins in other ethnic groups envy over the achievements of the Finns. So whose Copper Country is it? Well, first and foremost, of course, it belongs to those who presently inhabit it, a third of whom are of Finnish ancestry. But secondary, perhaps, it also belongs to those whose roots are on that copper range. Perhaps the Copper Country also belongs on some small ancestral level to the hundreds of thousands of descendents whose ancestors spent a generation or two on that “Interior Ellis Island.”

(Intro 1) Ninth Census

of the United States, Vol. I: The Statistics of the Population of the

United States, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872.

Close

(Intro 2) Ninth Census

of the United States, Vol. I: The Statistics of the Population of the

United States, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872.

Close

(Intro 3) Ninth Census

of the United States, Vol. I: The Statistics of the Population of the

United States, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872.

Close

(Intro 4) Quoted

in Angus Murdoch, Boom Copper: The Story of the First U.S. Mining Boom

(1943; reprinted Hancock: Book Concern, 1964), 201.

Close

(Intro 5) Twelfth

Census of the United States, 1900, Census Reports, Volume I, Part I,

Washington, DC: United States Census Office, 1901.

Close

(Intro 6) Ninth Census

of the United States, Vol. I: The Statistics of the Population of the

United States, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1872.

Close

(Intro 7) Statistics

of the Population of the United States at the Tenth Census, (1880) Washington:

Government Printing Office, 1883.

Close

(Intro 8) Report

on the Population of the United States at the Eleventh Census: 1890,

Part I, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1895.

Close

(Intro 9) Twelfth

Census of the United States, 1900, Census Reports, Volume I, Part I,

Washington, DC: United States Census Office, 1901.

Close

(Intro 10) Thirteenth

Census of the United States, Vol. I: Population 1910, Washington: Government

Printing Office, 1913.

Close

(Intro 11) Senate

Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants

in Industry, 61st Cong., 2nd Sess., 1910, S. Document 633, 86.

Close

(Intro 12) Employment

Records, Papers of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, Copper Country

Historical Collection, Michigan Tech University, Houghton Michigan.

Close

(Intro 13) Emily

Greene Balch. Our Slavic Fellow-Citizens. New York, Charities Publication

Committee, 1910, quoted in Francis E. Clark. “The Croats

in Croatia and in America.” in Old Homes of New Americans: The

Country and the People of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy and Their Contribution

to the New World. New York: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1913.

Close

(Intro 14) Anna

Brock, Chelsea Cole, Erin Klema, Jonathan Pohl, and Jenna Rickmon, “Diversity

in Calumet, Michigan, 1910,” research project for Michigan History,

Honors Program, Central Michigan University, May 2006, 11.

Close

(Intro 15) Calumet

and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground

by nationality on July 14, 1913 and September 29, 1914, Papers of the

Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, box 350, folder 7, Copper Country Historical

Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Intro 16) Calumet

and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground

by nationality on July 14, 1913 and September 29, 1914, Papers of the

Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, box 350, folder 7, Copper Country Historical

Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Intro 17) Calumet

and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground

by nationality on July 14, 1913 and September 29, 1914, Papers of the

Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, box 350, folder 7, Copper Country Historical

Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Intro 18) Calumet

and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground

by nationality on July 14, 1913 and September 29, 1914, Papers of the

Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, box 350, folder 7, Copper Country Historical

Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Intro 19) Thirteenth

Census of the United States, Vol. I: Population 1910, Washington: Government

Printing Office, 1913; Fourteenth Census of the United States, Vol. III:

Population 1920, Washington: Government Printing Office, 1922; and Fifteenth

Census of the United States, Vol. III: Population 1930, Washington: Government

Printing Office, 1932.

Close