An Interior Ellis Island (Print Version)

Keweenaw Ethnic Groups

The Poles

Close

Abstract

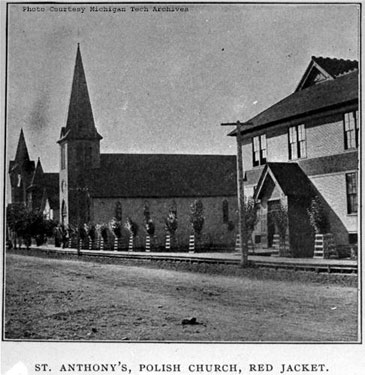

Although 2.5 million immigrants came to the United States from Poland between 1880 and 1924, Poles never established a particularly large presence in the Copper Country. Most who came to the Keweenaw worked as nonskilled underground laborers and mining companies used non-union Polish labor during the 1913-1914 strike to keep many mines operating. Although relatively small in number, the Polish immigrant community in Copper Country was strongest in Calumet and its cultural activity revolved around the Catholic Church. Poles built St. Anthony’s on Seventh Street, which also served as the meeting hall for Polish fraternal and benevolent organizations like the Stanislaus Kostli Benevolent Society. Unlike other ethnic groups, the Polish community declined quite rapidly in the early Twentieth Century.

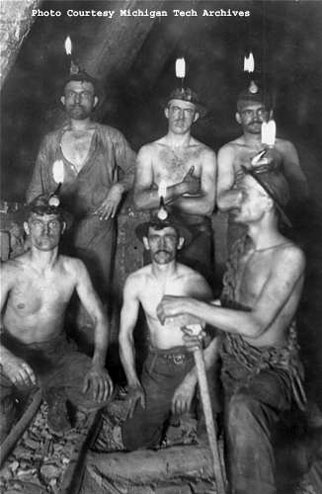

| Miners Underground Image #: Nara 42-142 |

During the last half of the nineteenth century, Poland, like to most of Europe, underwent the capitalist transformation of agriculture. This shift toward market-oriented agriculture demanded greater mechanization and thus capital investment. This process placed tremendous economic pressure on small landholders, who, because they lacked capital, increasingly could not compete in a market with larger landowners. Simultaneously, mechanization reduced the need for their labor as well as the labor of their less fortunate neighbors who were landless peasants. As such, the capitalist transformation of agriculture in Poland produced large numbers of Poles who either became unemployed or underemployed (surplus units of labor) or small landholders with insufficient land to survive. In search of work, or “for bread” (za chlebem) (Pol 1), many such Polish peasants were forced to migrate to areas with labor shortages in Europe and the United States.

The economic transformation in Poland provided the push factors for Polish emigrants, but it was another economic transformation, the pull factors, that determined their destination (Pol 2). During the last half of the nineteenth century, the United States expanded and industrialized, which produced a great demand for labor, a significant proportion of which was meet by Polish immigrants. Between 1880 and 1924, 25 million immigrants arrived in the United States; of this number, the Poles accounted 2.5 million or 10 percent (Pol 3). The Poles became a significant immigrant group in almost every important industry and as such large Polish immigrant communities developed in every major American urban center. It is not surprising that Michigan’s Copper Country and its mining industry also attracted Polish immigrants. What is surprising, however, is the relatively small numbers of Poles who migrated to the Copper Country, standing in shape contrast to their large numbers and percents in Michigan’s other urban and industrial centers and their large numbers and percents in other American mining communities.

A 1909 Report of the Immigration Commission estimated the Polish community in Calumet to number around 1,000 with another 300 Poles living in Mohawk (Pol 4). In comparison to other immigrant communities in the Copper Country, the Polish community was comparatively small. As such, little is known about this Polish immigrant community. Recently, however, David Siwik has produced a comparative study of Polish immigrant communities in Saginaw, Kalamazoo and Calumet, Michigan (Pol 5). In doing so, Siwik has established a community profile of the Calumet Poles and has raised important questions about its relatively small size. Determining the size of any Eastern European immigrant community in the United States is made difficult by the U.S. Census manuscripts, which enumerated individuals by place of birth not ethnicity. Thus, various Slavic ethnic groups are either mis-enumerated as Austrians, Russians or Germans. This mis-enumeration makes it even more difficult to identify a Polish immigrant community during the end of the eighteenth century. The German (Prussia), Austrian and Russian empires partitioned Poland and thus Poles are often mis-enumerated as Germans, Austrians and Russians depending upon their specific home in Poland. Siwik’s study, however, by applying surname and “mother tongue” analysis to the census manuscripts, identified 614 Poles living in Calumet in 1910 (Pol 6). Three-quarters of the Calumet Polish community emigrated from German controlled Poland, which stood in sharp contrast to the Saginaw and Kalamazoo Poles who were principally drawn from Austrian and Russian controlled Poland (Pol 7).

The 1909 Report of the Immigration Commission offers a statistical profile of Poles on the Keweenaw. More than three-quarters of the Polish immigrants interviewed had lived in the United States for period greater than twenty years (Pol 8), suggesting that most had worked somewhere else in the United States before migrating to the Copper Country. Prior to their immigration to the United States, the overwhelming majority had worked as agricultural laborers in Poland (Pol 9). Of the Polish male workers interviewed for the report, two-thirds were married with 80% of the married men having their wives living with them (Pol 10). According to the report, of the 5,000 plus foreign-born male workers interviewed in the Copper Country, nearly a quarter (23 %) had left the United States at least once since their initial entry (Pol 11), presumably, returning to their sending communities in Europe (Pol 12). Of Poles interviewed in the Copper Country, however, less than two percent had returned to Poland (Pol 13), suggesting that this Polish immigrant community in America was seen as permanent. Corresponding to this hypothesis, while 71% of the foreign-born male workers interviewed in the Copper Country had either become naturalized American citizens or had filed papers to do so, all the of the Polish male workers interviewed for the report had done so (Pol 14).

The primary occupation of Poles in the Copper Country was mining. In 1910, sixty-three percent of Polish immigrant workers in Calumet were directly employed at the mines, nearly exclusively as underground laborers (Pol 15). In July 1913, prior to the strike, the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company employed 156 Poles, constituting seven percent of its underground workforce (Pol 16). In September 1913, when C&H attempted restart mining operation, about a third of Poles refused to return to work and remained on strike (Pol 17). During the strike, however, it appears that C&H employed a large number of Poles as strikebreakers. By February 1914, the number of Poles employed by C&H swelled to 488, or 18 percent of its underground workforce (Pol 18) The increase of Poles at C&H during the strike, over 300 percent, was greatest of any ethnic group (Pol 19). Prior to 1910, the Quincy Mining Company had hired no Poles (Pol 20). In the decade from 1910 to 1920, however, Quincy hired 143 Poles, accounting for nine percent of its hires in that decade (Pol 21). As previously noted, Siwik’s study established that three-quarters of the Calumet Poles migrated from German controlled Poland; conversely, at Quincy, only five percent of the Poles it hired migrated from German controlled Poland (Pol 22), while 64 percent emigrated from Austrian controlled Poland and 31 percent from Russian controlled Poland. This difference suggests that the Poles at Quincy were more recent immigrants, as emigration from Poland’s German, Austrian and Russian controlled areas were not simultaneous. Emigration from German controlled Poland began in the 1870s and peaked around 1890, while mass emigration in Austrian controlled Poland began in the 1880s and from Russian controlled Poland in the 1890s (Pol 23).

| St. Anthony's, Polish Church, Red

Jacket, MI Image #: MTU Neg 04072 |

The entire population of the Copper Country declined after 1910, but that decline, while nearly unremitting, was gradual. This was not the case for the Calumet Polish immigrant community, which lost half its population from 1910 to 1920, from 614 to 306. In the next decade, 1920 to 1930, its numbers shrunk to just 45 (Pol 28). Such dramatic decreases in population transcend natural decrease and offers evidence to a significant out migration of the Calumet Poles. Thus, many Poles used the Copper Country as an interior Ellis Island, that is, a long-term, but not permanent, entry point into the American economy and society.

Buczek, Daniel. “Polish Americans and the Catholic Church,“ Polish Review 21 (1976): 39-61.

Bukowczyk, John J., ed. Polish Americans and their History: Community, Culture and Politics. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 1996

Bukowczyk, John J., And My Children did not Know Me: A History of Polish Americans. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1987.

Morawska, Ewa. “For Bread With Butter: Life Worlds of Peasant-Immigrants from Central Europe,” Journal of Social History 17 (April, 1989): 387-404.

David Siwik, “International Labor Migration into Michigan: The Polish-Immigrant Communities of Saginaw, Kalamazoo and the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, 1900-1930,” MA Thesis, Department of History, Central Michigan University, 2005.

(Pol 1) John J. Bukowczyk, And My Children did not Know Me: A History of Polish Americans. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1987), 11.

Close

(Pol 2)John J. Bukowczyk, And My Children did not Know Me: A History of Polish Americans. (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1987), 12.

Close

(Pol 3)Victor Green, “Poles,” in The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Stephen Thernstrom, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), 792.

Close

(Pol 4)Senate Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industry, 61st Cong., 2nd Sess., 1910, S. Document 633, 82-83.

Close

(Pol 5)David Siwik, “International Labor Migration into Michigan: The Polish-Immigrant Communities of Saginaw, Kalamazoo and the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, 1910-1930,” MA Thesis, Department of History, Central Michigan University, 2005.

Close

(Pol 6)David Siwik, “International Labor Migration into Michigan: The Polish-Immigrant Communities of Saginaw, Kalamazoo and the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, 1910-1930,” MA Thesis, Department of History, Central Michigan University, 2005, 83.

Close

(Pol 7)David Siwik, “International Labor Migration into Michigan: The Polish-Immigrant Communities of Saginaw, Kalamazoo and the Keweenaw Peninsula of Michigan, 1910-1930,” MA Thesis, Department of History, Central Michigan University, 2005, 85.

Close

(Pol 8)Senate Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industry, 120.

Close

(Pol 9)Senate Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industry, 121.

Close

(Pol 10)Senate Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industry, 96.

Close

(Pol 11)Senate Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industry, 171.

Close

(Pol 12)For a detailed examination of return migration, see: Mark Wyman, Round Trip to America: the Immigrants return to Europe, 1880-1930, Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1993.

Close

(Pol 13)Senate Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industry, 171.

Close

(Pol 14)Senate Committee on Immigration, Reports of the Immigration Commission: Immigrants in Industry,, 101.

Close

(Pol 15)Siwik, “International Labor Migration into Michigan, 94.

Close

(Pol 16)Calumet and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground by nationality on July 14, 1913 and February, 1914, Papers of the Calumet and Hecla Mining Company, box 350, folder 7, Copper Country Historical Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Pol 17)Calumet and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground by nationality on July 14, 1913 and September 29, 1914.

Close

(Pol 18)Calumet and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground by nationality on July 14, 1913 and February 1914.

Close

(Pol 19)Calumet and Hecla Mining Company spreadsheet indicating men working underground by nationality on July 14, 1913 and February 1914.

Close

(Pol 20)Employment Record Cards, Quincy, 1890-1920, Papers of Quincy Mining Company, Copper Country Historical Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Pol 21)Employment Record Cards, Quincy, 1890-1920, Papers of Quincy Mining Company, Copper Country Historical Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Pol 22)Employment Record Cards, Quincy, 1890-1920, Papers of Quincy Mining Company, Copper Country Historical Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Pol 23)Bukowczyk, And My Children did not Know Me, 11.

Close

(Pol 24)Polk’s Houghton County Directory 1899-1900, (Detroit: R.L. Polk and Co. 1899).

Close

(Pol 25)Houghton County Articles of Incorporation, Copper Country Historical Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Pol 26)Polk’s Houghton County Directory 1899-1900, (Detroit: R.L. Polk and Co. 1899).

Close

(Pol 27)Houghton County Articles of Incorporation, Copper Country Historical Collection, Michigan Tech University.

Close

(Pol 28)Siwik, “International Labor Migration into Michigan.”

Close