An Interior Ellis Island (Print Version)

Keweenaw Ethnic Groups

The Chinese

Close

Abstract

Although it was at one time the largest of Michigan’s

Chinese immigrant communities, the Chinese community in the Copper

Country was never numerically large and certainly never became as significant

as those in mining locations in the American West. Large-scale Chinese

immigration into the United States began around 1850, with landless

peasants and laborers pushed out of the Southeastern Chinese provinces

for California, which was experiencing an enormous labor shortage.

Little is known of the Chinese community in the Copper Country, but it appears to have been a microcosm of the larger Chinese American experience: serving the society while being excluded from it. The Copper Country Chinese were nearly entirely engaged in the laundry business with a few gift shops and groceries. Immigration laws prohibited Chinese women from entering the country, so Chinese in the region were almost exclusively male. Sadly, most of our understanding of this group comes through a few scant photographs and anecdotal evidence.

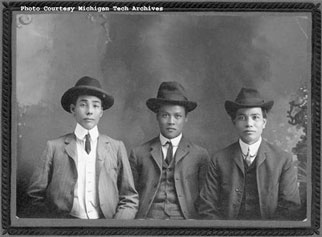

| Oriental Laundry Men Image #: Nara 42-173 |

Michigan’s Copper Country experienced immense immigration from Europe, but it also attracted “strangers from a different shore (Chin 1).” The Chinese community in the Copper Country was never very large, probably numbering only one hundred, and as such very little is known about it. Given, however, that it was Michigan’s largest Chinese community during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Chin 2), it certainly merits some examination. The Chinese who migrated to the Copper Country were part of a much larger nineteenth-century exodus from China. During the second half of the nineteenth century, the Chinese Empire experienced a rapid decline. Land ownership increasingly became concentrated in the hands of few wealthy elites at the expense of the peasants. Western imperialism add to this economic dislocation as it accelerated China’s decline, producing a breakdown in central political authority and ensuing economic chaos. This economic disorder forced millions to emigrate from southeastern China to Southeast Asia and to North and South America (Chin 3). Large-scale Chinese immigration into the United States began around 1850 when landless peasants and laborers where pushed out of the Southeastern Chinese provinces of Fukien and Kwangtung and pulled to California which experienced an enormous labor shortage.

While Chinese immigrants supplied much of the backbreaking labor for the early economic development of California, the construction of transcontinental railroad saw the first wide scale use of Chinese labor outside California. The project was exceedingly labor intensive and this tremendous labor demand could not be met by white labor. An estimated 14,000 Chinese worked on the building of the transcontinental railroad as well as trunk lines throughout the western United States. After the completion of the transcontinental rail link, the Chinese settled in western railroad towns and mining communities (Chin 4). Indeed, until 1880, the Chinese numerically dominated Butte, Montana, the other great nineteenth-century America’s copper district (Chin 5).

The Chinese presence in the United States, however, clashed with America’s nineteenth-century concept of “manifest destiny,” which argued for the racial superiority of whites (Europeans) to justify westward expansion (Chin 6). The Chinese, of course, had always experienced racism and racial discrimination in the United States, but as long as the United States required their labor, they were tolerated. This changed, however, when a sufficient supply of white labor migrated westward; in short, the Chinese were no longer needed. The ensuing labor market competition between the Chinese and whites produced a Chinese Exclusion Movement as whites petitioned congress to prohibit Chinese immigration into the United States. This was accomplished in 1882 with the Chinese Exclusion Act, making the Chinese the only ethnic group ever to be specifically banned from entering the United States. Chinese Americans responded to this Act and the racist mindset that produced it, by avoided direct labor market competition with whites and by entering into businesses such as Chinese restaurants, laundries, grocery stores and gift shops that did not directly compete with white merchants (Chin 7).

As stated earlier, little is known of the Chinese community in the Copper Country, but it appears to have been a microcosm of the larger Chinese American experience: serving the society while being excluded from it. The Copper Country Chinese were nearly entirely engaged in the laundry business with a few gift shops and groceries (Chin 8). The 1910 Federal Census Manuscript for Calumet offers a few further details of this community. Because of various laws that had prohibited Chinese women from entering the United States (Chin 9), the Calumet Chinese were exclusively male (Chin 10). The majority of had been born in China and those who were not born in China were born in California (Chin 11). The ranged in age from twenty to sixty and were single, with one except, a Mr. Chin who had married a women of German ethnicity in 1906. All of the foreign-born Chinese were naturalized citizens and most, not surprisingly, had become citizens in 1882.

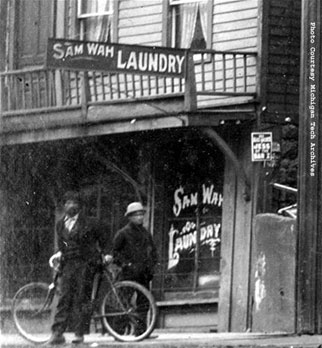

| Downtown Houghton Image #: No Neg 10-18-2005-001 |

Historian Arthur Thurner writes of parents threatening their children with being sold to the local Chinese proprietors to be butchered for chop suey (Chin 12). One boy recalled being frightened to pick up his father’s laundry at Ngan Lee’s shop, only to discover that Lee was friendly and jolly man (Chin 13). Views of the Chinese were often more explicitly racist as was the case of a Ontonagon newspaper which reported in 1907 that the town had “one chink and like most of his ilk he has an inquiring mind and thirst for the coin of the realm . . . He is not adverse to turning a few cartwheels in other lines [but] washee washee is his regular vocation (Chin 14).” In 1943, the Daily Mining Gazette reported that “the last of the celestials” had left Calumet. Ngan Lee, a thirty-year resident who had been in ill health for some time, had retired and moved to Chicago to live with sister. The brief article concluded, “ Ngan’s familiar little shambling figure will be missed by those who daily saw the friendly celestial making his calls at the business houses (Chin 15).”

Further Reading:

Hsu, Francis L. K. American and Chinese: Passage of Difference. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press, 1981.

Steiner, Stan. Fusang: The Chinese Who Built America. New York: Harper & Row, 1979.

Sung, Betty Lee. Mountain of Gold: the Story of the Chinese in America, New York, 1967.

Takaki, Ronald. Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans. New York: Penguin Books, 1990.

Wong, Bernard P. Chinatown: Economic Adaptation and Ethnic Identity of the Chinese. Singapore: Chopmen Enterprise, 1982.

(Chin 1) For the standard work on Asian Americans, see Ronald Takaki’s Strangers from a Different Shore: A History of Asian Americans, New York: Penguin Books, 1990.

Close

(Chin 2) The Thirteenth Census of the United States, Vol I. Population, General Nativity, and Foreign Population.

Close

(Chin 3) H. M. Lai, “Chinese,” in The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Stephen Thernstrom, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), 218.

Close

(Chin 4) H. M. Lai, “Chinese,” in The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Stephen Thernstrom, ed. (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1973), 219.

Close

(Chin 5) Timothy O’Neil, "Miners in Migration: The Case of Nineteenth-Century Irish and Irish American Copper Miners," in New Directions in Irish American History, Kevin Kenny, ed., (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2003) 133.

Close

(Chin 6) H. M. Lai, “Chinese,” in The Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, 220.

Close

(Chin 7) Bernard P. Wong, “Chinese,” in American Immigrant Cultures: Builders of a Nation, David Levinson and Melvin Ember, eds. (New York: Simon & Schuster Macmillan, 1997), 156.

Close

(Chin 8) Polk’s Houghton County Directory, (Detroit: R.L. Polk and Co.), volumes from 1895 to 1912.

Close

(Chin 9) Bernard P. Wong, “Chinese,” in American Immigrant Cultures: Builders of a Nation, 159.

Close

(Chin 10) The Thirteenth Census of the United State: 1910--Population, Manuscript for Village of Red Jacket.

Close

(Chin 11) The Thirteenth Census of the United State: 1910--Population, Manuscript for Village of Red Jacket.

Close

(Chin 12) Arthur W. Thurner, Strangers and Sojourners: A History of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula ( Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994) 153.

Close

(Chin 13) Arthur W. Thurner, Strangers and Sojourners: A History of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula ( Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994) 153.

Close

(Chin 14) Alma W. Swinton, I Married a Doctor: Life in Ontonagon, Michigan from 1900-1919 (Marquette, MI, 1964) quoted in Thurner, Strangers and Sojourners, 335.

Close

(Chin 15) Daily Mining Gazette, 28 October 1943.

Close