|

Setting the Scene An Interior Ellis Island Keweenaw Ethnic

Groups |

This project is funded in part by Michigan Humanities Council, an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities

|

Keweenaw

Ethnic Groups

~The Croatians~

Abstract•••I•••Article Contents•••I•••Further Reading•••I••Image Search•••I•••Source Notes

Abstract Croatian immigrants often lived in crowded boardinghouses, with individuals from the same village forming cooperative households to share expenses. During the 1913 Strike, Croatians distinguished themselves by their support for strike and the leadership they provided their fellow striking workers. Croatians joined with Slovenes build Catholic churches and were also active in supporting cooperative stores.

Croatians are a South Slav people who are closely related to Slovenians and Serbs, but separated by history, language and religion. Croatians and Slovenians are largely Roman Catholic, while the Serbs are primarily Eastern Orthodox Catholics. Spoken Croatian is nearly indistinguishable from Serbian but Croatian is written in the Latin alphabet while Serbian is written in the Cyrillic alphabet (Croat 1). The Congress of Vienna (1814-1815), which concluded the Napoleonic Wars, placed all of what is present day Croatia within the Austrian Empire. Croatia, however, was not a single administrative district, as the section of Croatia that had joined with the Kingdom of Hungary in 1102, was not united with the newly acquired Croatian-inhabited Dalmatian coast of the Adriatic Sea known as Dalmatia (Croat 2). In 1867 the Austrians (Germans) and the Hungarians (Magyars) reached a compromise that created a Duel Monarchy, or the Austro-Hungarian Empire, in which Germans and Magyars enjoyed equal status and worked together to block the nationalist and economic aspirations of Croatians and other Slavic ethnic groups within the Austro-Hungarian Empire. The push factors that produced Croatian emigration varied but land pressure, that is an economic cause, was the primary reason. Given Hungarian domination of Croatia, however, many Croatians viewed the cause of their emigration as political, paralleling the experience of other Slavs who lived in the Russian, Austrian or German Empires. While many in Croatia grew alarmed at the large out migration, the German-Magyar government in Vienna was not displeased by the emigration as it was increasingly alarmed by the Slavic nationalism developing within the Austro-Hungarian Empire (Croat 3). Because of their access to the Adriatic Sea, Dalmatians began emigrating in the 1840s, but mass emigration from the interior of Croatia did not begin until 1880. This mass Croatian emigration was facilitated by improvements in transportation, that is, the completion of rail line from the Adriatic port of Fiume into the interior region of Lipa-Krbava (Croat 4). The total number of Croatians who immigrated into the United States during this period of mass emigration is estimated at between from 400,000 to 600,000. Following Poles and Czechs, Croatians are the third largest Slavic ethnic group in the United States (Croat 5). In her seminal work Our Slavic Fellow-Citizens, Emily Greene Balch quoted from the notes of a Croatian schoolteacher and offered us a glimpse into the often hidden human side of emigration: Today they are telling in the village that fifteen are going to Fiume tomorrow by the early train – men, women, and young girls on their way to America . . . Toward evening they can be seen hurrying from house to house, taking leave of those that they love. Who can say that there will ever be another meeting for them? It is very late before they have finished these visits, and the family waits for them with impatience. With impatience, how else, when this evening or rather the few hours still left are so short. This is the last supper at home. There is no going to bed, for at three they must start for the station, as the train goes at four . . . With what anxiety and joy do they wait for the news from the agent that their dear ones have reached New York in safety. Their relatives are already expecting them, and the journey can be peacefully continued in their company. Our people generally go to Michigan. In one town there are so many that our people call it "New Lipa (Croat 6)." That one Michigan town, that "New Lipa,” was Calumet. Although Pittsburgh eventually attracted the largest number of Croatian immigrants and developed as the center for Croatian culture in America, Calumet had the distinction of being the first significant Croatian settlement in the United States (Croat 7). A 1909 Report of the Immigration Commission estimated the Croatian immigrant community in Calumet to number around 2,000, the third largest immigrant group behind only the Finns and the Cornish (Croat 8). The Report interviewed 500 Croatians and presented a statistical profile of the Croatian immigrant community in the Copper Country. As one might suspect, two-thirds had been engaged in agriculture prior to their emigration (Croat 9). Ninety percent of Croatians interviewed had immigrated to the United States within the past nine years, that is, between 1900 and 1909 and were as a group the most recent arrivals in the Copper Country (Croat 10). Perhaps corresponding to this fact, the report noted that Croatians, as a group, were the youngest immigrant workers in the Copper Country, with the majority being in their 20s (Croat 11). While two-thirds of the Croatians interviewed were married, only one-third of the married men had their wives living with them in America. This was the lowest percent of all immigrant groups surveyed (Croat 12). Conversely, and perhaps because of this fact, the Croatians, with 24%, were second to only the Cornish with 28% in their percent of those who had left the United States at least once since their initial entry (Croat 13), presumably, returning to their sending communities in Europe (Croat 14). Croatian immigrants in the United States tended to live in crowded boardinghouses (Croat 15). Frequently, Croatians from the same village would form cooperative households that were modeled on the communal households in Croatia known as zadruge (Croat 16). The advantage to living in a boardinghouse was that it allowed Croatian immigrants to pay less for housing and thus accumulate capital. With the money they saved on housing, Croatians could pay to bring family members to America, finance their own return visit, or perhaps purchase land back in Croatia (Croat 17). Saving such money, of course, came at the expense of an immigrant’s personal comfort. A small study of 248 dwellings in Calumet, which used census data and Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps to calculate dwelling size, suggests that the Croatians experienced exceeding cramped living conditions. While the average per-person living space for all households in the study was 260 square feet (Croat 18), the 40 Croatian immigrant households experienced lowest per-person living space in the study, a mere 113 square feet (Croat 19). Kim Hoagland’s innovative work has taken us beyond such numbers and offers a detailed examination of a Croatian boardinghouse. Her study focused on the Putrich home, the site of the Seeberville murders during the 1913 Copper Strike, and reconstructed the daily living conditions of its residents. Far from being a collection of strangers, at least 12 of the 17 inhabitants were related and thus this boardinghouse consisted of an extended family that provided a comforting familiarity to these Croatians as they adjusted to their new lives in America(Croat 20). In Addition, Hoagland’s study demonstrated how the Putriches, by living frugally and sacrificing personal space, were able to accumulate capital, which was “a strategy for home ownership (Croat 21).” In 1917, the Putriches moved to the Illinois coalfields and bought a house, free and clear, and resided in that house for the remainder of their lives (Croat 22). During the 1913 Strike, the pivotal event in the Copper Country’s history, Croatians more than any other ethnic group, distinguished themselves by their support for strike and the leadership they provided their fellow striking workers. When the Calumet and Hecla’s Mining Company attempted to resume underground operations in September 1913, an astonishing 94% of Croatians continued to strike, compared to only 40% of the total workforce (Croat 23). Croatians and Finns, with 63%, were the only ethnic groups that had a majority of their workers who refused to return to work (Croat 24). By the middle of December, 86% of C&H’s Croatian workforce still remained on strike, and, as such, they were the only ethnic group that had a majority of their workers out on strike (Croat 25). By the end of February 1914, when the strike was clearly lost, 84% of the Croatians continued to strike; the Finns with 24% were the nearest ethnic group showing such solidarity (Croat 26). As further evidence of Croatian solidarity during the strike, they stood alone among the major ethnic communities in having none of its members become deputies for C&H (Croat 27).

Needless to say, local newspapers supported the mine owners and reported such events as funeral of Putrich and Tijan with much bias—they did not even bother to spell Tijan name correctly. Tijan’s white hearse and bridal party were not seen as a symbolic upholding of Croatian tradition but rather as superstition and used as further evidence as to the essential backwardness of the Croatians. The bias of newspaper, that is, their language, is often difficult for historians to deconstruct. Non-coverage, however, of important events is easy to uncover. The national press gave the strike extensive coverage. The New York Times, Boston Globe and Wall Street Journal produced several hundred articles on the strike but did not consider the murder of two Croatians worth mentioning. Such glaring absences are brought into sharper focus when contrasted with the murders of Thomas Dally, Arthur Jane and Harry Jane, that is, the murder of three Cornishmen. The New York Times and Boston Globe thought the Jane-Dally murders worthy of front-page news (Croat 30).

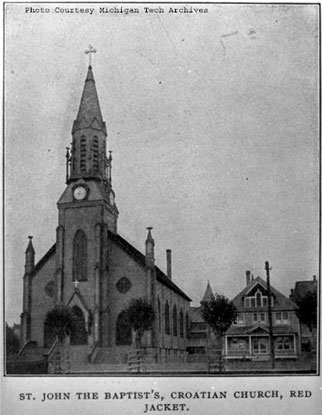

Croatians, like all large immigrant communities in the copper country, formed a number of religious, cooperative, fraternal, beneficial and social organizations that helped maintain community cohesion while simultaneously assisting with their transition into the larger American society. The Croatians joined with Slovenes in Calumet to build St. Joseph’s Catholic Church. Eventually, however, Croatians established their own Catholic Church in Calumet: St. John the Baptist. The Croatian community in Calumet also built a cooperative store in 1905 as did Croatians in South Range, establishing the Croatian Workingman’s' Cooperative in 1907. South Range Croatians also contributed to the creation of two additional cooperatives in 1907: partnering with Slovenes to form Slovensko-Hrvosko Cooperative Company and with Italians to establish the South Range Cooperative Store (Croat 33). In addition to religious and cooperative organization, Croatians in the copper country also created mutual benefit societies that collected dues and served as an insurance pool to be extended to members in times of financial stress, such as an illness, an injury or death. Between 1892 and 1915, Croatians in the copper country established five such societies: the Croatian St. John the Baptist Benevolent Society (Calumet, 1892), the Horvacko-Dobrotvorno Drustoo St. Roko. Rirus, Katholic Society (Calumet, 1897), the Croatian Benevolent Society—Vinodolac (Calumet, 1901), the St. Matijas Society of Baltic (Baltic Mine, 1909); and with Slovenes, the Slovenian-Croatian Union (Calumet, 1901) (Croat 34). Many such national mutual benefit societies developed into national fraternal organizations, as was the case with the National Croatian Society (NCS) that was established in Pittsburgh in 1894. It was through such fraternal organizations that immigrants and their children located housing, found work, organized into political blocks and meet their perspective mates. Croatians in Houghton County formed three chapters of the NCS: the St. Jeronim Assembly (Calumet, 1900), St. Froljen Assembly (Calumet, 1905), and the St. Michael Assembly (Painesdale, 1908) (Croat 35). Emily Greene Balch. Our Slavic Fellow-Citizens. New York: Ayer, 1969. George Prpich. The Croatian Immigrants in America. New York: Philosophic Library, 1971. E. Shapiro. The Croatian Americans. New York: Chelsea House, 1989. Alison K. Hoagland. ”The Boardinghouse Murders: Housing and American Ideals in Michigan’s Copper Country in 1913.” Perspectives in Vernacular Architecture: The Journal of the Vernacular Architecture Forum 11 (2004), 1-18

|

Copyright © 2004 - 2007

MTU Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections, J. Robert

Van Pelt Library, All Rights Reserved |