Abstract

Finnish immigration to Michigan’s

copper district grew to become the most populous

ethnic group with an enduring cultural identity.

Kuparisaari, “copper island,” went beyond

the Finnish immigrant identification of the island

that comprises the northern half of the Keweenaw

Peninsula to a symbolic island of landing, an Ellis

Island. Michigan’s Copper Country is recognized

as focal to Finnish immigration to America, the birthplace

of many Finnish-American institutions religious,

political and educational. This “island” includes

both settlements in growing industrial urban communities

like the Quincy, Calumet & Hecla and Champion

mining settlements, and cleared forestland for traditional

Finnish agriculture as in Toivola, Tapiola, Elo,

Pelkie, and Waasa; Finns settled north and south

of the Portage Waterway that bisects the peninsula.

Perhaps more than any other immigrant group, the

Finnish communities in the district were bisected

into divisions of politics and faith. The Finns who

immigrated to the copper mining district held to

a pietistic Laestadian (Apostolic) Lutheran belief,

to the state-sanctioned Lutheranism of Finland (Suomi

Synod) or rejected faith altogether. Within these

divides of conscience of faith was a wide political

spectrum: conservative to liberal adherents, resolute

temperance advocates and active radical socialists.

The social and economic conditions that emigrants

left in northern Scandinavia and the Duchy of Finland

influenced these allegiances and beliefs.

The

Finns who came to the mining district by 1914 had

never known a self-governing Finland. Finland functioned

subordinate to some six centuries of Swedish governance

superceded by Russian imperialism from 1809. From

the disenfranchised laborers of Vaasa in the west,

the collapsing wood-ship building and tarring industry

along the Bothnian coast, and the famines in the

north, Finns from the Russian Duchy of Finland and

from northernmost Norway and Sweden lived in a cycle

of poverty which grew bitterer by the mid-19th century.

Famine from 1862 to 1868 was followed by increasing

economic and political Russian oppression. Regarding

the famine, John Kolehmainen records its severity:

I remember, though a child

When frost stole the harvest.

We suffered hunger then,

There was no food to be blest.

Mother cried until her death,

Father sank, sorrowed,

Tears streaked his furrowed cheeks,

As bread in vain we begged and borrowed (Finn

1).

But failed crops were just one cause of famine and

poverty. In the 1890’s, a Russian Prince Kropotkin

described the Finnish tenant farmers’ desperate

poverty, a poverty from rent and taxes:

He gnaws at his hard-as-stone rye-flour cake

which he bakes twice a year; he has with it a

morsel of fearfully salted cod and a drink of

skimmed milk. How dare I talk to him of American

machines (presumably for farming efficiency),

when all that he can raise must be sold to pay

rent and taxes (Finn

2)?

A small middle class of professionals, prosperous

shopkeepers, larger land and industry holders belonged

to a long-established Swedish-speaking privileged

caste and a smaller still Finnish bourgeoisie, often

shunning the language and lifeways of the majority.

As late as the mid-19th century, Finns campaigned

to make the Finnish language officially co-equal

with Swedish, an official recognition that would

take much longer to be adopted as the culture of

business and government. Meanwhile, Lonnroth and

Sibelius preserved and created Finnish cultural traditions

with the commitment of the epic Kalevala to paper

and the composition of complex lyrical music, respectively (Finn

3).

However, the rise of nationalist Finnish sentiment

ran up against an intensified Russian oppression.

Since 1878, a law made the young men of the Duchy

of Finland eligible for compulsory service in the

imperial army and navy. A Russification program of

Governor-General Nikolai Bobrikov, appointed by the

Czar in 1898, made its boldest incursion with the

February Manifesto of 1899 (Finn

4). The Finnish Diet, a body of governance

for the Duchy, lost all meaningful power and the “Great

Address,” a petition with over half a million

signatures to revoke the manifesto, was ignored by

the Kremlin (Finn

5).

The overpopulation, poverty, larger number of landless

people and uncertainty of employment of southern

Ostrobothnia, the region of origin for most emigrants

to America from 1867-1892, seems to have formed the

primary reasons to uproot and move. During that period,

sixteen thousand people emigrated from Ostrobothnia

and about fifteen thousand from all the rest of Finland

combined (these figures do not include ethnic Finns

from Norway and Sweden). Ninety percent of emigrants

from Ostrobothnia worked in agriculture and ten percent

had other vocations (Finn

6). The development of industry in southernmost

Finland shifted the labor opportunities away from

rural agriculture. These economic opportunities in

industrial centers in Finland and America were in

contrast to the brutal upheaval of a population that

had nearly doubled during the preceding two generations

in northern Finnish regions such as Ostrobothnia

and Satakunta (Finn

7). Most sought employment in the growing

industries in southern Finland but a small portion

would seek opportunities in Michigan’s copper

district (Finn

8).

However, it was the Finnish (kvaenar) and Lapp (finnar

or saami) émigrés from Norway’s

northernmost Finmarken province whose recruitment

by the Quincy Mining Company, coinciding with the

height of famine in northern Scandinavia, who would

be the first to immigrate to the copper district.

Adding to 18th century emigrants from Finland to

northern Norway, Norwegian officials and English

mine managers lured Finns in the 1830’s and

1840’s (Finn

9). These immigrants were almost exclusively

followers of Pastor Lars Levi Laestadius (Finn

10). In Norway they would engage in fishing,

agriculture and copper mining. Abstinance from drink

distinguished these devout Lutherans from many of

their Finnish neighbors and may have contributed

to the English mine-owners and Norwegian officials’ choice

to employ them in the mines and other industries

of the sparsely-populated Finnnmarken or Ruija. They

joined not only 18th century Finns in Finnmarken

but an ancient Lapp (Saami) pattern of wintering

their reindeer herds on Norwegian lands and islands

of the district.

In 1864, the Quincy Mining Company recruited about

20 Finns and 80 Norwegians to Hancock, Michigan.

The Quincy Mine official, Christian Taftes, who spoke

Finnish, Norwegian and Swedish fluently and had emigrated

from the Tornio Valley, contracted the workers at

the English-owned Kaafjord and Alten mines. On May

17, 1865 a sailing ship from Trondheim, Norway departed

with 30 more kvaenar (Norwegian Finns) destined for

Quincy Mine. Landing in Quebec, a lake steamer brought

the all-male workforce into port at Hancock on the

eve of Juhanipaiva, St. John’s Day, a Finnish

holiday on June 24th (Finn

11). Although between only 700 and 1,000

Norwegian Finns immigrated, they introduced through

correspondence with family and friends in Norway,

Sweden and Finland the possibilities for relocating

in Michigan and in Minnesota. For Michigan’s

copper district, the Amerikan Suomilainen Lehti,

or the “American Finnish People” newspaper,

estimated in 1880 that fully one half of ethnic Finns

harkened from Norway and Sweden (Finn

12).

By the 1870’s some 3,000 Finns had left Scandinavia,

and from 1880 to 1886 alone, 21,000 emigrated. By

about the mid-1880’s, more were emigrating

from provinces in the Duchy of Finland itself. From

then until 1893, 40,000 more left and in that year

alone an additional 9,000 departed, most to the United

States. Although the next four years would see a

steady rate with 16,000 additional applicants, the

year of the February Manifesto’s introduction

in 1899 brought a record application for passports,

12,000, a number that would grow to a climax of 23,152

applicants in 1902 (Finn

13). The 1893 to 1920 total number of emigrants

was 274,000 people, most prior to 1914 and a small

minority being Swedish-Finns.

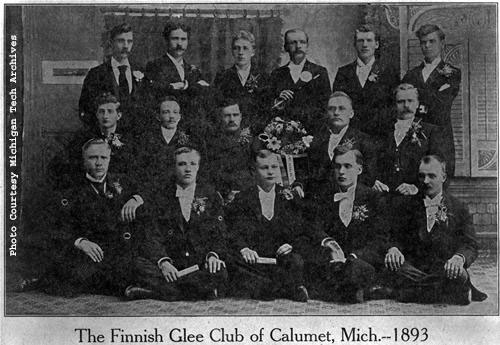

Although the first Finns arrived in Hancock for

Quincy Mining Company employment during the U.S.

Civil War, it was the rising star of Calumet & Hecla

Mining Company who would begin to offer the greatest

opportunities for employment both in the mine and

in surrounding business. By 1880, in the mine’s

settlement area around the Village of Red Jacket

Finns made up approximately one in five residents

or 1,800 of 9,000 persons (Finn

14). Finnish-American historical geographer

Arne R. Alanen with Suzanna E. Raker made astonishing

findings regarding Finnish institutions by this same

year:

Despite relatively small numbers, Finnish

immigrants quickly established several ethnic

institutions in Calumet, the community that emerged

as their earliest pesapaikka, or “nesting

place,” in America. By 1880 Calumet’s

Finns supported a newspaper, two churches, a

mutual aid society, a literary society, a printing

company, a lending library, a land company and

two mining companies. Finns also operated a general

store, a watchmaker-shop, nine public saunas,

and a saloon in Calumet (Finn

15).

Perhaps most remarkable is the number of institutions

that reflect the literacy and value of education

to a broad rather than just elite cadre of Finnish

immigrants. In addition to the early rise of Finnish-American

leadership in many arena’s of public education

and the first of what would be many Finnish language

newspapers (i.e. Amerikan Suomilainen Lehti published

in Calumet) in the 1870’s, the establishment

of Suomi College, now Finlandia University, in Hancock

in 1896 became the most potent symbol to both the

Finnish Lutheran communities. Suomi College was a

seminary primarily but by the early 20th century

was venturing into broader educational goals. Today

Finlandia University’s Finnish American Archives

and the Finnish-American Heritage Center’s

cultural performances and arts instillations form

the hub of the district’s Finnish immigrant

consciousness.

The high literacy of Finns came as a surprise to

many in America, both immigrant and native born,

who presupposed that like their own communities,

poverty and illiteracy often went hand-in-hand. Many

disparaged the Finns as “Mongolians,” during

a time when social-Darwinists had it that Asian,

like African, ancestry was a sub-human genus. Oskar

J. Larson was a retired U.S. Congressman from Minnesota

when he responded to a racist editorial in the Sault

Evening News in January 1932. Larson was born in

Oulu, Finland in 1871 and brought to Calumet, Michigan

in 1875, rising to the elected office of Village

of Red Jacket attorney before moving into politics

in Minnesota. In Larson’s letter-to-the-editor

he recognized the obvious use of the “Mongolian

theory” by the editor to denigrate Finnish

mental abilities and then stated, “illiteracy

in Finland is less than one per cent. It is practically

nil. In our own country it is six per cent. In your

state of Michigan it is three per cent.” English

author Ernest Young states in his 1930’s publication

Finland, Land of a Thousand Lakes, “no one

who knows anything about the Finns will deny that

they are the best educated nation in the world. Neither

Germany nor America can claim equality with them

in this respect.”

Educated or not, Finnish immigrants often felt the

sting of discrimination on a level greater than their

European-immigrant neighbors. Many mine managers

found the Finns to be resistant to integration and

slow to learn English. Local society in general harbored

suspicions about the Finns, the politics of some

and their unfamiliar customs. A settler from 1887

stated, “the old settlers looked down upon

them with the same sort of aversion as the west coast

people do on the heathen Chinee (Finn

16).” But ethnic discrimination

did not end with such statements of ignorant fear.

Corporate mine management throughout the Lake Superior

region noted the Finns disproportionate involvement

in radical labor and unionism. In letters to the

company President, Agent Charles Lawton blamed Finns

for a 1906 strike, which resulted in lost production,

increased wages and other financial losses to the

company (Finn

17). Calumet & Hecla Mining Co. General

Manager James MacNaughton wrote plainly to the Commissioner

of Immigration at Ellis Island and the U.S. Secretary

of Commerce and Labor, “we do not want Finlanders (Finn

18).”

The degree to which Finnish immigrants were distrusted

and often shunned by mine management and even the

communities into which they moved was disproportionately

high compared to their immigrant neighbors. Alanen

posits that one “unique and often controversial

manner” by which Finnish immigrants dealt with

the difficulties of life in an industrial society

occurred with the change in the loyalties and beliefs

of immigrants through the immigration period. The

conservative Lutheran orientation of the 19th century

immigrant community became augmented by the arrival

of radicalized early 20th century Finnish immigrants (Finn

19). Although socialist ideologues were

small in number in the district, particularly by

comparison to their representation amongst Finnish

immigration to Minnesota, they found a place for

labor unrest and conflict with management in the

Finnish immigrant communities employed in the industrial

mines.

In 1913, when the districts most effective work

stoppage was organized, Finnish workers played a

significant role. For instance, when the workers

organized a party for the children of strikers on

Christmas Eve at the Italian Hall in the Village

of Red Jacket and a false-call of “fire” resulted

in the stairwell-trampling and death of 73 people,

more than 50 of the deceased had Finnish surnames,

a tragic census of labor activism. Alanen and Raker

summarize the most controversial Finns who made up

a part of the final stage of immigration to the district:

During the major period of immigration an

appreciable number of the Finns who had been

radicalized by their Czarist homeland, or had

been part of Finland’s trade union movement,

joined the migration stream. These Finns, at

the least, were familiar with the basic tenets

of socialism and often expressed a willingness

to challenge the prevailing capitalist norms

of early twentieth-century America (Finn

20).

Disillusionment with industrial mining for some

and the high percentage of Finns who came with an

agricultural vocation lead many Finns to choose farming

over mining in a district where most immigrants found

the poor soil and short growing season unsuitable

for the task. The pietistic Laestadian (Apostolic)

Lutheran church leaders extolled the virtues of farming.

Alanen and Raker note an editorial directed to the

largely Laestadian readership of the Amerikan Suomalainen

Lehti that farming is the “wisest and most

natural kind of work (Finn

21).” Finnish immigrant J. H. Jasberg

in Hancock was anxious to sell land to immigrant

farmers. He admonished Finnish-immigrant men to make

sure they were wed to a healthy, hardworking wife

before starting a farm. He also gave a perspective

on the opportunities for farming that might have

brought rebuke or even smiles to the faces of immigrants

from other countries when he stated that the district

had a “healthy climate (Finn

22),” amongst other things, for the

prospective farmer.

Samuel Mattila came from northern Finland at the

age of 16 in 1902, the year of greatest emigration

from Finland. A Laestadian Lutheran, he, his four

siblings and his parents moved to Cokato, Minnesota.

When he moved to Michigan’s Copper Country,

he first worked loading copper onto Lake Superior

ships. However, his intention was to farm and in

1916 he bought a farm in Toivola, meaning “place

of hope,” and married the daughter of one of

that Finnish community’s four pioneer families,

Laura Johnson. Alanen and Raker state that the saying,

Oma tupa, oma lupa, or “One’s own home,

ones own freedom,” resonates throughout the

Finnish-American communities of North America (Finn

23). And indeed Samuel saved for this freedom.

Samuel’s father had been a Lapp reindeer herder,

his eye removed by an antler and a thumb missing

from an arctic lasso accident in winter. Samuel was

old enough when he left arctic Finland to have honed

skills for the challenges of far-northern farming.

Gordon Mattila describes his father Samuel:

He knew how to snare a partridge or a rabbit

using a root of a tree like a fine rope, and

how to set fishing weirs. He talked of building

a pulka, the sled pulled by reindeer, and of

making skis. He knew how to make healing salve

out of balsam pitch. He tried to never waste

anything and used what he had in sometimes ingenious

ways (Finn

24).

The Mattila family’s stories are characteristic

of many Finnish pioneers.

In 1920, a friend of Jacob Johnson wrote an epitaph

in his memory. The deceased immigrated to Baraga

County, founding an agricultural settlement known

as Kyro, after his placed of birth in Finland, and

later renamed Pelkie.

A strong-looking Finn has just come with his

tools and a lunch to the wilderness about ten

miles north of Baraga. He has felled his first

giant pine where his home will be built. The

sun is setting in the west. The man sits on the

fallen tree and glances about him. He sees nothing

but forest, dense wilderness, all around him.

He remembers the farms of Kyro (Finland) with

their fields of waving grain and their flower-fragrant

meadows. As his thoughts flew back there, a beautiful

church, two of them, appeared in his mind’s

eye: an ancient one out of an old fairy tale

and the other new and modern (Finn

25).

Finnish farms were carved out of the woods, like

Jacob Johnson’s and as pioneers in Toivola

or Tapiola did, or built where the copper mining

industry’s landscape-transforming support industry,

logging, left denuded forestland. The east side of

Otter Lake, for instance, was settled by Finns on

land cleared by French Canadian lumberjacks (Finn

26).

The rural backdrop to the settlements around copper

mines is the forest and the farms that Finns, primarily,

developed there. But this landscape is not static.

The once very traditional, even distinct Finnish-parrish

forms, found on kuparisaari are disappearing. Like

the Finnish traditions of hearth and home within

the once urban settlements of the district, the farms

too are transforming. Their distinctive forms, like

the lifeways of immigrant descendents, are integrating

to new norms, distant from historic practices. Perhaps

in this way, the Finnish immigration story to America

most parallels European immigration patterns. A pattern

of assimilation taught in school, rewarded at work

and encouraged by the broader culture operates in

tension with family tradition and ethnic institutions. |

Further

Readings:

Arnold R. Alanen & Suzanna E. Raker, “From

Phoenix to Pelkie: Finnish Farm Buildings in the

Copper Country,” in New Perspectives on Michigan’s

Copper Country, Kim Hoagland, Erik Nordberg and

Terry Reynolds, eds., Hancock, Michigan: Quincy

Mine Hoist Association, 2007.

Arnold R. Alanen, “Finns and the Corporate

Mining Environment of the Lake Superior Region,” Michael

G. Karni, ed., Finnish Diaspora II: United States,

The Multicultural History Society of Ontario, Toronto,

1981.

Arnold R. Alanen, “The Planning of Company

Communities in the Lake Superior Mining Region, “ Journal

of the American Planning Association, No. 45, July

1979.

Michael Karni, ed., The Finnish Experience in

the Western Great Lakes Region: New Perspectives,

Migration Studies, Turku University, Institute

of Migration.

Michael Karni, ed., Finns in North America: Proceedings

of Finn Forum III, Migration Studies, Turku University,

Institute of Migration.

A. William Hoglund, “Finns,” in Harvard

Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, Stephan

Thernstrom, ed., Cambridge, Mass.: Belknap Press

1980.

A. William Hoglund, Finnish Immigrants in America,

1880-1920, New York, Arno Press “Scandinavians

in America” collection, 1979.

Armas K. E. Holmio, History of the Finns in Michigan,

translated by Ellen M. Ryynanen. Edited by Philip

P. Mason & Charles K. Hyde, Detroit: Wayne

State University Press, 2001.

Ralph J. Jalkanen, ed., The Finns in North America,

Michigan State University for Suomi College, Hancock,

1969.

Reino Kero, Migration from Finland to America

in the Years between the United States Civil War

and the First World War, Turku, Finland, 1974.

Richard Vidutis, “Finnish settlement architecture

in Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula: Adaptation,

evolution and restoration of forms,” Ph.D.

dissertation, Indiana University, 1991.

Gordon J. Mattila, Stories of the Early Years;

The Mattila Farm, Toivola, Michigan, 1904-2004,

Atlantic Mine, Mich., Shenanigan Press, 2004.

John I. Kolehmainen, The Finns in America: A Bibliographical

Guide to Their History, Hancock, Mich., 1947.

|