|

Setting the Scene An Interior Ellis Island Keweenaw Ethnic

Groups |

This project is funded in part by Michigan Humanities Council, an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities

|

Keweenaw

Ethnic Groups

~The Slovenes~

Abstract•••I•••Article Contents•••I•••Further Reading•••I•••Image Search•••I•••Source Notes

Abstract Slovene settlers such as Jozef Vertin and Peter Ruppe established themselves in the local commercial, political, religious, and industrial landscape. The larger majority of immigrant Slovene hired into mining companies as trammers and other low-level occupations. Like other immigrant groups, Slovenes established ethnic-based institutions such as taverns, churches, and fraternal lodges to preserve their language and culture. |

||||||

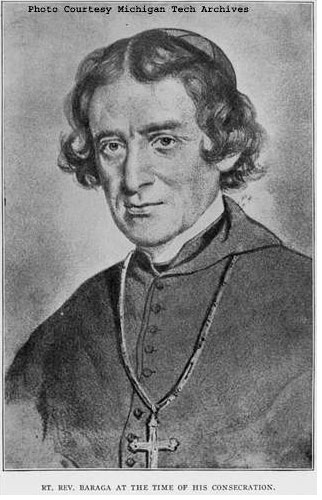

The first Slovene to call the Keweenaw home left rather large footsteps for his compatriots to follow. It was the winter of 1843, and Frederic Baraga was earning his nickname as the Snowshoe Priest for his dedicated service to the small number of English, French Canadian, German, and Ojibway Catholics living in Michigan’s remote Upper Peninsula. Father Baraga’s adventures and successes inspired thousands of other Slovenes in the 19th century to leave their homeland for the United States; Calumet was one of their chosen destinations. There, they organized the country’s first Slovenian benefit society, built an imposing and beautiful church, and established a place for themselves in the Copper Country’s commercial, political, religious, and industrial landscape. Slovenes are a South Slavic people whose territory was ruled by the Hapsburg dynasty from 1335 to the collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1918. Their language and culture distinguish them from Italians, Croatians, Hungarians and other near neighbors. The exception to this are the inhabitants of the Prekmurje region bordering Hungary, who developed a dialect and orthography that was influenced by the Hungarian language; this served to differentiate them from the majority of other Slovenian speakers. Historically, Prekmurje also set itself apart in its choice of religion: while a vast majority of Slovenes were Roman Catholics, Prekmurje was predominantly Protestant (Slov 1). Typically, land was held in small family farms of a few acres or more. Large families were common, and younger sons were frequently required to seek their fortunes elsewhere. Economic conditions were in fact the most common reason for leaving Slovenia between 1850 and 1914, as the country had no established industry to accommodate men and women needing a source of income. While a small number of Slovenes had immigrated to the United States during the 18th century, most came during three distinct periods in the 19th and 20th centuries. The first occurred between 1880 and 1914; Austria-Hungary’s involvement in World War I effectively halted that wave of out-migration. Immigration resumed after the war in 1919, but new, restrictive laws passed by Congress in the early 1920s saw numbers decline. The final major Slovenian immigration to the United States occurred in 1945-1956, and was largely a response to political events that followed World War II. Total numbers of immigrants are difficult to determine: census and immigration records frequently identify Slovenes as Austrians – or Yugoslavians after 1919 – or group them with Croats. It has been suggested that the total number of Slovenian immigrants who stayed in the United States between 1845 and 1945 are in the range of 250 to 350 thousand. The first significant arrival of Slovenes is heralded by one individual in particular: Father Baraga. He was born in Dobernice in 1797 and landed in the United States on December 31, 1830. Baraga was particularly interested in ministering to Native Americans; he established missions in Ohio, downstate Michigan, and Wisconsin before arriving in L’Anse in 1843. Following the Treaty of LaPointe (1842) he purchased the land around the mission at L’Anse and deeded it to the Ojibway in order to prevent their removal to the west (Slov 2). As the only Catholic priest in the Upper Peninsula, he worked hard to serve the spiritual needs of many nationalities and languages, traveling from Ontonagon to Sault Ste. Marie, and north up along the Keweenaw. During this time, he also compiled the first known Ojibway grammar. By 1853 he was elevated to Bishop of Michigan’s Northern Peninsula. Bishop Baraga’s legacy was honored not only by having a county named after him, but also by the number of Slovenian priests whom he inspired to come to the United States. It has been suggested that of all groups who came here, this pattern – priests preceding lay immigrants – is unique to the Slovenian immigrant experience (Slov 3). By the late 19th century, pioneering priests were serving the growing number of Slovenes who immigrated for work in the Upper Peninsula’s copper and iron mines and lumber industry of the upper Midwest. One of the more notable clerics was Reverend Joseph Buh, who came to the US in 1864 and began ministering to Slovenes in northern Minnesota. He started the first Slovenian newspaper in 1891 – Amerikanski Slovenec – which is still being published today (Slov 4). As was the pattern with many groups, the majority of immigrants were young men who later sent for wives, children, and other family members; friends and acquaintances from their home towns often followed, and old neighborhoods were recreated.

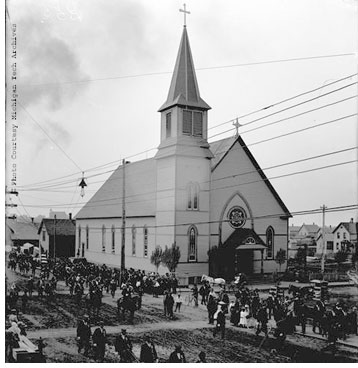

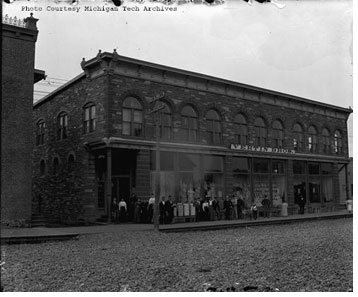

Given its association with Bishop Baraga, its rich copper mines, and its need for laborers, it is no wonder that the Keweenaw became the destination of choice for ambitious young Slovenes. In fact, it has been argued that Calumet is the oldest Slovene community in America (Slov 5). Writing in 1912, Reverend Trunk identified Jozef Vertin and Peter Ruppe as Calumet’s first Slovene settlers. After carting and selling goods to the increasing number of miners in the Keweenaw, the two established businesses in Hancock and Calumet, or Red Jacket as it was then known. The four-story Vertin Brothers department store in Calumet soon became a major retail outlet for miners, their families, and the growing community. In 1875, residents of the newly incorporated village elected George Vertin as alderman to serve with Ruppe, the first mayor. Ruppe also assumed the responsibilities of the village’s first fire chief. By the 1890s, thousands of other Slovenes were joining them, looking for work in the deep-shaft mines of the Copper Country. Most of them came from rural backgrounds, typically from the provinces of Carniola and Styria (Slov 6). Having little opportunity for formal education and lacking English speaking skills, mining companies hired these new arrivals as trammers and in other low-level occupations; demonstrating proficiency allowed them slowly to move up the hierarchy and become miners. This experience was shared with other immigrant groups. Like them, many Slovenian families provided space in their own home for boarders to earn extra money. For about 20% of a worker’s income, they would be provided a bed, meals, and laundry service. Women increasingly assumed an economic role in the community as they were by and large responsible for managing boarding house operations. This influenced women’s migration, as well; female relatives were often brought over from the old country to help with the extra domestic work that a boarding house entailed. Like other immigrant groups, Slovenes established ethnic-based institutions such as taverns, churches, and fraternal lodges to preserve their language and culture. Fraternal organizations and benefit societies provided social security in an era when the government did not; dues bought insurance as well as membership in a club where music, dance, and linguistic traditions could be maintained. Given the fact that it was such an early Slovenian-American community, it is no surprise that Calumet was also the site of the nation’s first Slovenian benefit society: the Calumet Slovenian Catholic St. Joseph Benevolent Society was founded there in 1883 in order “to provide aid and relief to its members when in need.” (Slov 7) Other local societies included the Lodges of St. Peter and of Sts. Cyril and Methodius. National organizations were formed later, including the Carniolan-Slovenian Catholic Union (Chicago, 1894), South Slavonic Catholic Union (Ely, 1898) and the Slovene National Benefit Society (Chicago, 1904). St. Joseph’s church in Calumet was built for the Slovenian community, and was served by Slovenian priests. Built of locally-quarried Jacobsville sandstone, it replaced an earlier structure that was shared with Croatians. Renamed St. Paul the Apostle in 1963, it is still an active parish whose priests minister to the descendents of Calumet’s Slovenian, Croatian, Italian, and other immigrants.

Taverns also served an important social function for immigrants, and frequently catered to an ethnic clientele. A glance through Houghton County’s Polk Directory from 1905 reveals that many were named for their proprietors, such as Tambolini’s and Curto’s. 1905’s directory also indicates that Paul Shaltz (also spelled Schaltz) operated a saloon in his residence. While no name is officially printed in the book, his daughter Mary Shaltz Zunich remembers quite clearly that Naradna Gostilna - “National Saloon” in Slovenian – was printed in large letters above the door. Located as it was on 7th street near the train depot, the saloon was readily identifiable by Slovenes arriving in Calumet. Zunich believes that her father served as a type of informal agent for new Slovenian and Croatian arrivals, helping them find work and a place to stay, sometimes even in his own home: he and his Croatian wife also ran a boarding house for Slovenian and Croatian immigrants. In addition to running a tavern and hosting boarders, Schaltz was also an editor of a Slovenian newspaper (Slov 8). Not only did he take an interest in his fellow Slovenes, he also became involved in local politics; he was the man who in 1929 suggested that Red Jacket officially change its name to Calumet (Slov 9). Slovenians have been instrumental in the formation of the Keweenaw. As laborers, trammers, and miners, they contributed to the industrial development of the Copper Country. From Father Baraga to the Vertins, Ruppes, and Shaltzes, they helped build religious, commercial, and political legacies that still color Calumet’s culture and define its skyline. |

||||||

Cetinich, Daniel. South Slavs in Michigan. East Lansing, MI: Michigan State University Press, 2003. Susel, Rudolph. “Slovenes.” In the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, edited by Stephan Thernstrom, 934-942. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980.

|

Copyright © 2004 - 2007

MTU Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections, J. Robert

Van Pelt Library, All Rights Reserved |