|

Setting the Scene An Interior Ellis Island Keweenaw Ethnic

Groups |

This project is funded in part by Michigan Humanities Council, an affiliate of the National Endowment for the Humanities

|

Keweenaw

Ethnic Groups

~The French Canadians~

Abstract•••I•••Article Contents•••I•••Further Reading•••I••Image Search•••I•••Source Notes

Abstract

French Canadians have a long association with Lake Superior and the Copper Country, having visited the region as explorers, miners, and fur traders in the 17th century and later as lumberjacks, mill operators and surface work in the area’s mining industry. Many of Houghton County’s French Canadians lived in the village of Lake Linden, also called “Little Canada” or “Frenchtown” due to their overwhelming majority. Individuals such as Joseph Grégoire operated successful sawmill operations in the region and supported local French Canadian culture, including the Société St-Jean-Baptiste benevolent society, June 24 festivities to celebrate St. Jean Baptiste day, and French Canadian churches such as St. Anne’s in Calumet and the St. Joseph church in Lake Linden. |

||||||

French Canadians have been coming to the Copper Country

since Samuel Champlain first heard about it in 1610 (Fren

1). Arriving first

as explorers, miners, and fur traders in the 17th century, they later

came seeking work as lumberjacks and mining industry surface workers.

These occupations neatly reflect two distinct waves of French Canadian

immigration to Michigan: the first came before the American Revolution,

when the fur trade was in full swing, and the second – and

much larger – wave occurred after the Civil War when the Keweenaw’s

mining industry was rapidly developing (Fren

2).

Faith and family were emphasized over education as New France developed, and

society became distinctly stratified with a civil and ecclesiastical elite and

a rural, unschooled underclass of farmers and laborers who referred to themselves

as habitants. While they exercised a great deal of economic independence, habitants were not allowed to serve in government nor operate printing presses; the clergy

did not encourage political or educational activity and preached traditional

religious values of humility, chastity, and obedience (Fren

4). As Great Britain and France

battled for control of valuable North American territory through the 17th and

18th centuries, French Canadian culture continued to develop along these stratified

lines. Between 1780 and 1830, many French Canadians continued the tradition of trading and settling in Maine, New York, Vermont, and New Hampshire, and exploring the Midwest and West. Julien Dubuque established his eponymous city in Iowa in 1796; he was followed by Jean-Baptiste Beaubien (Chicago, 1813) and Laurent Salomon Juneau (Milwaukee, 1818) among others. A fluid border allowed many French Canadians to move back and forth between Quebec and the United States, but immigrants increasingly stayed in the United States after 1840. Numbers peaked between 1880 and 1895 as unfavorable economic conditions in Quebec induced many to find work in the milling and lumber industries of New England and the Midwest, including the Upper Peninsula. Despite leaving Canada, an emphasis on protecting their language, faith, and ties to Quebec remained. French Canadians were very early drawn to Michigan (Fren 7). Not only was there the allure of copper, the Upper Peninsula also presented a strategic geographic location and the animal resources to support the fur trade. Many of the earliest French Canadian settlements in Michigan are still thriving communities today: L’Anse on Keweenaw Bay was established as a mission by Jesuits in 1660, who also built communities at Sault Ste. Marie (1668) and St. Ignace (1671) (Fren 8). Downstate, French Canadians accounted for 80% of the non-Native population of Detroit when the United States government established a presence there in 1796. The French Canadian majority continued until about 1825, when they were outnumbered by Americans arriving through the brand new Erie Canal. By 1837, the fur trade was waning and French Canadians were less inclined to move to the newly created state of Michigan. Immigration picked up after the Civil War, when rapid industrialization created a need for laborers; once again, French Canadians came seeking opportunities in the Upper Peninsula. According to John Forster, “[t]he Canadian Frenchman could not be induced to become a miner (Fren 9).” Instead, he preferred to work in the woods, farming, or in business. Despite the fact that deep-shaft mining dominated Houghton County’s industry in 1900, it was second only to Wayne County in the number of residents who were born in French Canada (Fren 10). Michigan also had the largest number of French Canadians in the Midwest, and nationally lagged behind only Massachusetts, California, and Rhode Island. In Houghton County, they found work in mining company smelters and stamp mills, and as lumberjacks and carpenters. Many of Houghton County’s French Canadians lived in the village of Lake Linden, also called “Little Canada” or “Frenchtown” due to their overwhelming majority (Fren 11).

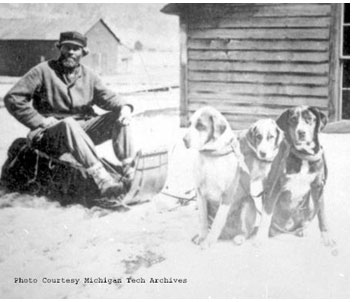

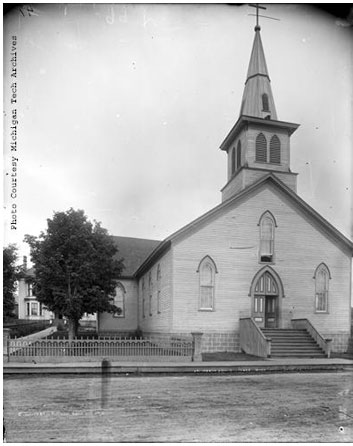

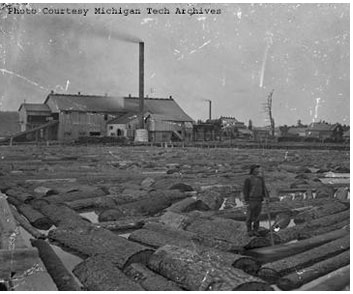

First settled in 1851, Lake Linden was at the heart of a booming lumber district with a thriving French Canadian community. French Canadians published newspapers, established churches and schools, and worked in sawmills. One of the most well-known individuals associated with that industry was Joseph Grégoire (Fren 12). Born in St. Valentin, Quebec in 1833, he came to Lake Linden when he was 21 years old. He found work as a woodsman, and in 1867 went into partnership with Louis Deschamps and Joseph Normandin. Together, they operated a sawmill until 1872 when Grégoire assumed sole ownership (Fren 13). Grégoire ultimately built a small empire consisting of mills, factories, and 65 thousand acres of timberlands (Fren 14). Grégoire also had a hand in constructing Lake Linden’s first church: St. Joseph’s was built in 1871 and dedicated to St. Joseph de Calasant. By 1883 the congregation numbered 1,800 and was overwhelmingly French Canadian. A larger church to accommodate the faithful was completed in 1912, still stands on Calumet Street, and hosts an active multi-ethnic congregation (Fren 15). French language newspapers included Le Courrier du Michigan (1912) and Le Franc-Pionnier, which began printing in 1875 (Fren 16). Le Courrier moved to Detroit in 1919, and stayed in print until 1957. Each newspaper was founded by men from Quebec who had immigrated to Michigan. While many of Michigan’s French Canadians were members of the Société de Lafayette, Union des Canadiens-Français Catholique, and International Order of Foresters, their most important benevolent society was the Société St-Jean-Baptiste (Fren 17). Based in Montreal, the Société in Michigan helped French Canadians maintain their culture, language, and ties to Quebec and mediate their assimilation into mainstream American culture. By 1900, chapters were located in several cities in the Lower Peninsula as well as Houghton, Hancock, Calumet, Lake Linden, and several other towns in the Iron Range. The Société and other French Canadian organizations held annual parades, picnics, and bonfires on June 24, St. Jean Baptiste day. Clearly, preserving their cultural traditions – survivance – was

a concern for the Keweenaw’s French Canadian immigrants.

As early as 1874, classes were being offered in Calumet for people

wanting to learn to speak and write French fluently (Fren

18). St. Anne’s,

an imposing French Canadian church, was built in 1900 in Calumet,

and restaurants operated by J.R. Jacques and Treffele Homier

during the late 19th century competed with several others in

Houghton County (Fren

19). Other traditions remained as well. Born in 1905,

Evelyn Othote Glesener remembered a French Canadian custom her

family practiced each New Year’s Day: children would speak

privately with their father, recounting all their misdeeds of

the previous year and then receive counsel on ways to improve

their behavior. Their session would end with the father granting

his blessing (Fren

20). Not only did Glesener recall how she and her siblings

would try to get their well-behaved brother to go first to ensure

their father’s good mood, but she also shared how important

the tradition was to teach “respect for family, for our

parents.” By speaking of the importance of faith and family

in maintaining ethnic identity, Glesener offers a local expression

of survivance (Fren

21). |

||||||

Barkan, Elliott Robert. “French Canadians.” In the Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups, edited by Stephan Thernstrom, 388-401. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1980. DuLong, John P. The French Canadians in Michigan. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press, 2003. ---. “Tracing French Canadians in Michigan’s Copper

Country,” French Canadian Genealogical Research in Houghton

County, Michigan. Monette, Clarence. The History of Lake Linden, Michigan. Lake Linden, MI: n.p., 1977. Sauer, Carl O. Seventeenth Century North America. Berkeley: Turtle Island, 1980. Thurner, Arthur W. Strangers and Sojourners: A History of Michigan’s Keweenaw Peninsula. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1994.

|

Copyright © 2004 - 2007

MTU Archives and Copper Country Historical Collections, J. Robert

Van Pelt Library, All Rights Reserved |