|

Though mining was the main employment draw for immigrants to the Keweenaw Peninsula, a number of other industries provided employment opportunities away from the mines. Many industries operated in support of mining operations; others were only peripherally associated with the mines. When immigrants and fortune seekers first came to the Keweenaw Peninsula in the mid 19th century, there was very little to offer outside of the copper mines. In 1864, the Michigan State Gazetteer described Hancock as a “post village” with a population of 1700, most of whom were “chiefly engaged in mining.” It boasted nine saloons and hotels, and one justice of the peace. Outside the village limits, “most of the township [was] an uninhabited wilderness, and a considerable portion of it covered with swamps.” Other than Quincy Mining Company, the only other industries in the township were a tannery and an ashery. The ashery produced potash, used for fertilizer and as a flux in the smelting process (NonMin

1).

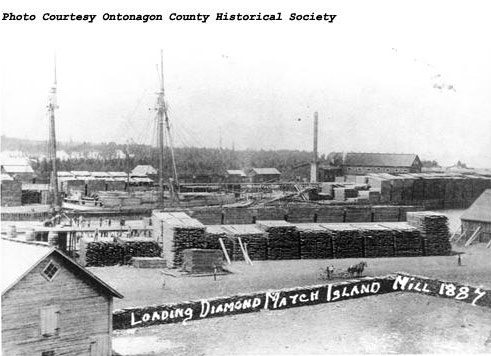

Immigrants and settlers had to figuratively carve their young society out of the remote wilderness, and this they did with determination. Lumbering was one of the earliest and most important industries in the Keweenaw, appealing to a workforce comprised heavily of Swedes, Norwegians, and French Canadians. Wood was used for building material and for fuel. Massive timbers were used as stulls, underground support for the hanging rock face left when miners extracted the copper-bearing ore. Early industrial structures such as shaft houses were made of wood rather than metal, and housing was needed for the myriad workers employed by the mines. Scandinavian lumbermen produced thousands of board feet from local timber used to build stores and residences throughout the area.

Another sought after local building material was stone. Occurring along the eastern side of the Keweenaw Peninsula, sedimentary deposits of what came to be known as Jacobsville sandstone caught the eye of English stonemason George Craig (NonMin

2). The Portage Entry Quarry operated several quarries in the Keweenaw, carving out blocks of sandstone that were used in commercial and residential buildings throughout the United States. Many of these grand and stately buildings still stand today, enduring monuments to the labor of the Finnish quarrymen of Jacobsville.

The mining companies had a large appetite for iron. Rock crushers and stamp shoes were used to break up thousands of tons of hard basalt year after year for processing in the smelters. Foundry workers were kept busy replacing worn out and broken machine parts. Three productive foundries, Portage Lake Foundry and Machinery Company, the Hodge Iron Foundry, and the brass foundry Ward and Williams, were located side by side at the Ripley waterfront, conveniently located near the Quincy, Pewabic, and Franklin mills (NonMin

3). The Hodge Iron Foundry, also called the Lake Superior Iron Works, boasted that their exclusive cold-forged stamp shoes received an award at the Columbian World Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Foundries manufactured the nuts, bolts, and miscellaneous hardware needed by mining companies and other industries to stay in business. Foundries also cast precision brass fittings and parts for machines.

By the early 20th century, railroad tracks criss-crossed the peninsula. Trains moved unrefined ore to the smelters, copper ingots to shipping docks, workers to their jobs, even children to school. Passenger cars transported people and products in and out of the area. In an area where roads were reduced to a morass of mud in the spring and blocked by drifts of snow in the winter, business depended on railroad trains to maintain contact with the rest of the world.

The great engines that powered the early mining machines ran on steam, making the Portage Lake Boiler Works a key player in area industry. Electrical power companies supplied energy to businesses and, at least early on, to residents in the major towns of the Copper Country. Rural electrification was complete until many years in the future. Peninsula Electric Light and Power Company was the first entity outside of the mining companies to supply power to consumers.

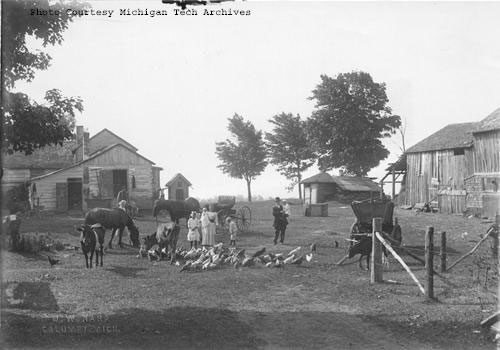

Agriculture was a challenge in the harsh climate of the Keweenaw, but it was a challenge relished by immigrants from northern Europe. Many families operated small farms during the summer and saw their men folk off to the mines during the cold winter months. Potatoes, strawberries, and hay emerged as dominant cash crops as the 20th century unfolded. Dairy cattle were also profitable.

A number of other industries ranging from large to small produced a variety of goods for the area’s inhabitants. A pair of early Houghton entrepreneurs, William Rainey and Harvey Parke, ran a tinware manufactory in the 1860s (NonMin

4). The firm of Prendergrast & Clarkson, operating out of the National Bank Building in Houghton offered engineering services for heavy structural contracts such as railroads and public works. M. Van Orden was a dealer in Portland cements, lime, brick, hair, and other builder’s material, at the turn of the century (NonMin

5). Chinese immigrants also found a place for themselves in the Keweenaw. An oriental fancy goods store, Hand You & Company, also operated a cigar factory on the premises that rolled fine tobacco for the discriminating smoker (NonMin

6).

The mélange of immigrants to the Copper Country in the 19th and 20th centuries contributed to a surprisingly diverse community and supported a wide range of industries and business. Many workers tried their hand at different professions until settling on one for good; many others took paying jobs in established companies, saving their hard won wages until the day they could purchase a piece of land and go into business for themselves as farmers. The present population of the Keweenaw still reflects this diversity and, in many ways, the transient nature of a populace in search of work and a place to call home. |